| deutsche Version | pictures | main page |

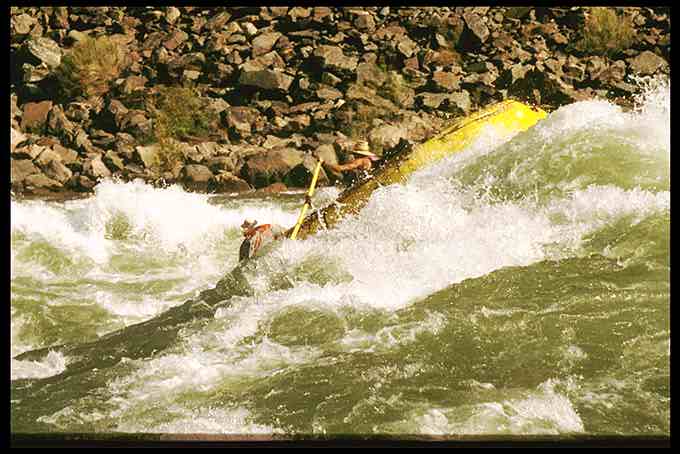

"Hold on!",--Charlie hardly needed to say it now. We tourists learned on the first day that there is only one catchphrase here in the white inferno of foamy ice-cold water of the Colorado river--"hold on!". Today is the second day. Nevertheless it cannot be ignored that we have problems. Charlie lost an oar and we're propelling with worrysome speed toward a sharp-edged rock.

House Rock Rapid, Mile 17: Strong rapids. The Colorado has its own scale. "Normal" rivers are rated on a scale from "one" to "six". "One" is absolutely still water. "Six" is just about impassable. On the Colorado the scale extends from "one" to "ten". House Rock Rapid runs from "nine"to "seven" depending on water levels. The Colorado is not a normal river. It has remained wild and hard to figure out even though it has been tamed somewhat. It has become a house pet, a machine for producing electricity.

What would Las Vegas and Phoenix be without the Colorado? Lost villages in the deserts of the Southwest United States. Only the river provides them with energy and water. Reservoirs--Lake Mead and Lake Powell--keep the glittering metropolises alive. The energy needs of Phoenix today determine the water level of the river. As much water is released from Lake Powell as the air conditioners in Phoenix require.

It is just that that makes tourism on the Colorado possible. Earlier the river roared through the gorge it had dug and only permitted its own dynamic life. The water level during the snow melts in the spring could be 30 meters higher than normal. Neither plants nor animals had a chance to settle here. Today the water levels vary by at most one meter. That makes a lot of things easier to figure out: rapids, available places for overnighting.

All the same, the Colorado remains coy. It is not easy to get near it. One of the few ways in is at Lee's Ferry, a few miles below the dam of Lake Powell. Lee's Ferry is "the" entrance into the adventures in the Grand Canyon if one doesn't want to be satisfied with the view from above. Here begin the river trips. From here is how the miles are counted.

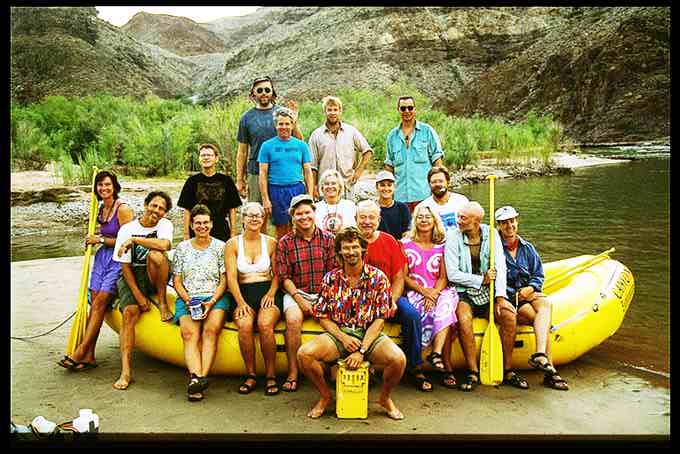

House Rock Rapid, Mile 17: A good 200 miles still lie before us. We, 12 tourists and seven river guides, are spread out on 5 boats.

One is a kitchen boat, steered by Mark, the cook. Three are oarboats, each rowed by a pro, which can carry a maximum of 3 passengers on board. And one is a paddleboat, in which 6 tourists can work under the direction of a paddle captain.

Jenn--Jennifer--is still a student and may give the cook a hand. Rudi is an exotic--he knows as little about rafting as we tourists. Nevertheless, he is making the trip and therefore is responsible for our artistic entertainment. Rudi is a musician. This kind of thing is a tradition on the Colorado--the philosopher, the writer, the artist is always along with the better organizations.

The trip lasts 14 days. Of course it is possible to do it faster. Most of the 21 different organizations which offer trips through the Grand Canyon travel the river with motor boats--giant rubber rafts which provide space for 2 dozen passengers and which can cover the stretch in less than half the time. On those one doesn't have to have the feeling of being cut off from civilization. With the smell of gasoline always in your nose and the noise of the motors in your ears, one may not listen to the songs of birds and the sounds of cicadas in the tamarisk bushes on shore. The canyon wren will certainly never waste on them his descending melody which sounds as if he is laughing at the little humans. And they will scare away the bighorns.

One does not have to rely on the filtered river water in order to cover the immense need for liquids in the desert. Ice-cold beer or soft drinks are always within comfortable arm's reach. We "natural people" develop quickly a feeling of superiority toward the "normal tourists" that we now and then encounter. So much eludes them...

All the same, we're all subject to the same laws. Whoever travels the Colorado must bring everything that he will need with him and everything that he has brought or produced along the way, he must take back out with him. Only footprints remain.

Two weeks in the rhythm of nature. The day lasts from morning until twilight. For the first time in decades, I live without a watch.

When the sun comes up, still hidden behind the walls of the canyon, the conch, a large seashell, sounds. Our crew uses it as a signal. The coffee is ready! We fill our plastic cups and gradually begin to work: We do our morning toilet (the bathroom is the river) and pack. The tent, put up in the evenings as a precaution against strong winds, has remained empty, but will be put away. Sleeping bags, in the bathwater warm night, were comfortable pads. Now they disappear in a waterproof rubber bag which came from the surplus inventory of the US Army.

The next signal--breakfast! Amazing, all the things that Mark can produce. Whoever believes that there are no blueberry pancakes for breakfast in the Grand Canyon deceives himself.

We load the boats. The crew is responsible for lashing everything down, but everyone must help. The last warning call: "Last call on water!" The water filter will be immediately packed and then only accessible again in the evening. Who hasn't filled his water bottles? "Last call on the unit!"--that is our toilet.

Who paddles today? Who gets into the oar boats? That becomes clear quickly every morning. It is also clear what will happen today: We will travel further down the river like every day. Toward noon we will land somewhere where there is shade and have lunch. With a great probability we will at some point steer for a side canyon and go hiking there. Hiking, however, can mean many things. For example, to move oneself about 100 meters to the Silver Grotto, swimming through ponds and climbing steep walls of sheer stone. Or take a completely "normal" four mile hike to the end of a canyon to bathe in the waterfall there and fill the water bottles again and again along the way in the mountain stream. Or climb a steep mountain and find 1000-year-old ruins, with a breath-taking look back. Perhaps Rudi will put his guitar on his shoulder and give us a concert in a place with particularly favorable acoustic conditions. But always in the plan is "frolicking"--to have fun. We will splash, bathe, jump from rocks or, upholstered by our lifevests, let a side river carry us along.

In any case we will get wet. Even the tamed Colorado is still a synonym for white water. There is a rule of thumb: 90% of the river through the Grand Canyon is quiet, 10% therefore turbulent water. And of that, 10% is dangerous rapids. Therefore only a good 2 miles have them. There boulders have accumulated from the side canyons from where they were washed into the river through erosion, storms and melt water. Patricia, called Trish, our paddle captain, sometimes doesn't sound calming at all in her directions: "We have 2 possibilities. Either we paddle hard or we ram the rock there in the middle."

Us against the river? No. Us with the river. We have no motor, which as long as it has fuel, can conquer the river. We have to rely on agreement. Have to follow the currents. Let ourselves be bagged. Accept that the waves bury us. With the paddles, depend on the waves because we have nothing else to depend on. Not to fall into a panic when the force of the water dumps us out of the boat.

The rapids always announce themselves in the same way. A rumble rises up in the distance, but at the same time the water becomes quieter. The boulders which lie underneath in the way below us all of a sudden dam up the river: When the pros stand up to "read the water" it is just ahead. Sometimes the preparation becomes a ritual: We land above the rapids and the guides decide among themselves on the best way. They do that when it can be really dangerous because the rocks lie just below the water surface--at Crystal Rapids or Lava Falls. But there are also real fun rapids, in which nothing can happen except that meter high waves smash around us and we can go swimming.

"We have a swimmer!" This cry of alarm sounds more than once. But the Colorado is mostly gracious. Almost always it keeps an eddy ready beside a foamy rapid in which the person thrown overboard can be fished out again and rescued. At dangerous places all the boats remain together in order to be able to help each other if necessary. In any case, the rescue action should not last too long. The water temperature is between 8 and 12 degrees celsius. To be sure the river is not responsible for that. The water of the Colorado in the Grand Canyon is ice-cold, deep water from Lake Powell. The air temperature in the canyon in summer varies during the day between 40 and 45 celsius. It is bearable nonetheless because the air is bone dry. A shower or swim in the rapids is all the same not an unwelcome cooling off.

Second half of July: We are in monsoon times; really every afternoon a thunderstorm unloads. The thermics of the canyon, hundreds of meters below the plateaus, produce in this season regular cool showers. On our trip the exception becomes the rule. We only experience one storm, but one that changes our region impressively. On the plateau above us rain accumulated in dried-out brook runs; all of which lead to the canyon. Water begins to drop, to trickle, to fall, to pour. Waterfalls develop and come down with incredible force. We are lucky that our camping place is only half washed away. Red-brown waterfalls loaded with sediment--the river changes color, the blue becomes rust red. Now for a few hours it deserves its name: Colorado.

In the late evening we will land somewhere on a sandbar and Tom will decide if we will overnight there. Tom is the leader of our group and his word rules. The desert does not appear to be a place for democracy. "Over here is where the kitchen will be, over there the toilet, and over there is the camping area." And that's that. Again the line will be formed to unload, the opposite from the morning. We are a disciplined troop; only when everything is on the beach that we will need for the night will each person grab his personal belongings and look for a sleeping place.

The sand is so fine and clean, better than any Caribbean advertisement, but it should not have any giant red ants--they can deliver a powerful bite. And one shouldn't unpack the sleeping bag until it really is time to go to bed in case one doesn't want to share it with a scorpion or rattlesnake. Otherwise there is little to do--the crew works now to prepare the dinner. To keep two weeks provisions for about 20 people each boat has a giant block of ice in the middle. The ice melts slowly and keeps the food amazingly fresh that we will be polishing off in the course of our trip. First fish, then fowl, meat in the third place, and there is always fruit and salad. Not until the last three days does Mark reach back for cans. The conch calls first for hors d'oeuvres, then for dinner and finally for dessert. Even in the desert delicious cakes can be baked.

Soon it will get dark. The air is animated. All the bats in the world appear to be meeting here. Their perfect sonar system lets them avoid any touching of the lightly dressed humans who sit on the beach or move on back to their sleeping places. They are silent and elegant and they lead their dance first 20 meters high, then 100 meters, then they are gone.

They have made place for the stars. The Milky Way, not at all visible for the normal city dweller, sometimes recognizable as a small band in areas where the lights of the world don't overwhelm the heavenly lights. But the Milky Way in the Grand Canyon is a branching cascade of lights. The closest earthly light sources are hundreds of kilometers away. A day on the river makes you tired. But because of those heavens we are often long awake. At some point we fall exhaustedly asleep because desire gives out. Who can still think of anything after the seventeenth shooting star?

"What's our age today?"

"Three Billion Years"

No one thinks of this as a strange communication . A trip into the Grand Canyon is a trip into the past. Into the history of our world. Into the childhood of our earth. In the case that Mother Earth today, after about 4 billion years, is grown up, then she was once a child. Or at best at the beginning of puberty. The Colorado has dug out her history as it cut through, to survive, a rock plateau that gradually rose layer upon layer being exposed in this way.

At the start, at Lee's Ferry, the river was bordered by walls that are perhaps 30 meters high. The red Kaibab-Formation there is "only" 250 million years old. After a week we will find ourselves in a canyon whose perpendicular walls extend to 1000 meters above us and which are more than 10 times older. These timeframes elude human feelings and it is impossible to imagine what was there then: A world of volcanic action and meteorites hitting the earth. The first single cell organisms fought for their life. How hard it was even for the rocks, one can see today. Even the granite is wounded, turned, folded.

We have traveled back in the history of the world, have long left the carbon behind us, that eon, in which life on earth exploded. The stage in which human life developed, we have not yet touched. The prehistoric canyon doesn't concern itself about us. It doesn't concern itself about anything. The cacti, the other succulents, the tamarisks, the bighorn sheep, the snakes, spiders and insects--they are simply there. Even the tourists, a maximum of 150 per day. The canyon is. It has long been. It will probably still be for a long time. It is indifferent to everything. Whoever has the strange idea of slowly going down the Colorado knows that somehow that is not just a vacation. That becomes a trip into the past. The past of whomever. Or a trip into oneself. Or into the Milky Way.

| deutsche Version | pictures | main page |